Here are two beliefs Dominic Cummings holds about Brexit. One: He believes it will help us to phone up Jeff Bezos and partner with him on creating a base on the moon, which will in turn enable us to industrialise space.

Two: He believes it can be delivered by using the same models of government that will inevitably be required to avoid an apocalypse brought on by either nuclear war or an artificial intelligence (AI) that decides to destroy the human race.

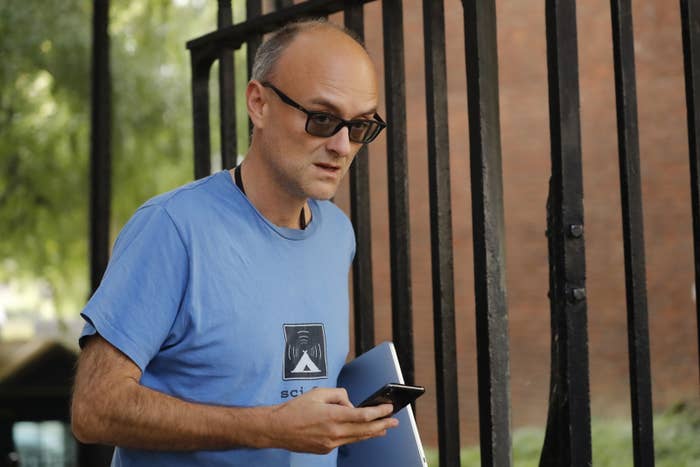

These two statements aren’t throwaway examples of his most outlandish claims. They’re significant elements of what Cummings, the prime minister’s most senior adviser, thinks about Brexit, as laid out in his blogs.

He has been publishing his thoughts online for the best part of half a decade. Whenever a new blog appeared on his site, Westminster reporters would skim through the thousands of words and focus on his attacks on Brexiteers, Remain campaigners, Tory MPs, and others. But now that Cummings is in Downing Street, his epic writings have become key source material for anyone trying to decipher how he really sees the future of Britain and Europe.

And the more one reads the blogs, the more one can see the outline of a Brexit plan for the Boris Johnson administration. They don’t just explain why Cummings thinks no deal is an option — they explain how and why he thinks Whitehall should actively work towards it.

Cummings’ influence on the machinery of government is already taking hold. A Whitehall insider told BuzzFeed News that the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra), which is on the front lines of no-deal planning, had even begun implementing initiatives similar to the “systems approach to delivery” he blogged about at great length before he arrived in Number 10.

The phrase means that rather than being considered in isolation, issues are considered in terms of how they connect. At Defra, rural land use, food, air quality, marine, and resources and waste are being examined to see how they affect one another.

Defra was, until recently, run by Cummings’ old boss and close confidant, Michael Gove, who is now in charge of no-deal preparations. In the face of a no-deal Brexit, the department has taken on a level of significance last seen during the foot-and-mouth crisis of 2001. Speaking of changes to the way its civil servants operate, “It’s not far off what [Cummings] would consider best practice,” said a source. When approached, the department refused to comment.

It may well be that Boris Johnson pulls back from the brink of no deal later this year — one of Cummings’ beloved “alternative branches” of history. Whatever happens, we have never had such insight into the thought processes of arguably the most important man in government shortly before he took up such a role.

The blogs are a frustrating read. They are overwritten, there are minor inaccuracies, and Cummings’ prose style is often closer to that of an embittered teenager scribbling in their diary than a government adviser. He deliberately avoids structuring arguments, stringing ideas together and entrusting the reader to make a connection between them. The blogs also contain scores of strong ideas and perceptive analyses, along with ideas that are far more fanciful, often in the space of a single paragraph.

This brings us to the proposed Jeff Bezos moon base: Cummings writes about it here, envisaging a post-Brexit Britain that is “the best place in the world to be for those who can invent the future,” which could “create whole new industries.” He says:

We could call Jeff Bezos and say, ‘Ok Jeff, you want a permanent international manned moon base, let’s talk about who does what, but not with that old rocket technology.’ No country on earth funds science as well as we already know how it could be done — that is something for Britain to do that would create real long-term value for humanity, instead of the ‘punching above our weight’ and ‘special relationship’ bullshit that passes for strategy in London.

He’s so taken with the idea that he revisits it here, citing the proposed call to Bezos as one of many “projects that could bootstrap new international institutions that help solve more general coordination problems such as the risk of accidental nuclear war.”

The lunar base, he adds, would assist in “a) basic science, b) the practical purposes of building urgently needed near-Earth infrastructure for space industrialisation, and c) to force the creation of new practical international institutions for cooperation between Great Powers”.

The moon base fits into a vision where Brexit is a gateway to greater international cooperation. It’s the same theme with the AI apocalypse: His views on the risk posed to humans by AI are laid out in detail here. The blogs repeatedly cite a 2011 interview with Deepmind chief scientist Shane Legg, who claimed “there is a 50% probability that we will achieve human level AI by 2028, a 90% probability by 2050, and ‘I think human extinction will probably occur’”.

This view isn’t particularly controversial among experts, but it comes in a 15,000-word piece that he initially claims is “not directly about Brexit at all”, yet repeatedly returns to the subject between sections on an obscure AI project in the Pentagon, 1970s warfare, modern drones, the AI arms race, systems management in China, and much more besides.

At one point he claims that the notorious £350 million for the National Health Service could be found “in days”, and goes on to describe an “extremely different ‘model of effective action’ to dominant models in Westminster,” which could push Brexit negotiations “in a different direction”.

Negotiating Brexit is a big, complex project, Cummings adds — and the management of “May/Hammond/Heywood/Robbins et al” has been “a case study in how not to manage a complex project” by failing to adequately prepare for no deal. Cummings feels that “systems management” is relevant to how Brexit negotiations should be done, avoiding nuclear war, and avoiding an AI apocalypse.

Thousands of words on government procurement, Chinese national planning, AI, and government spending follow, with Brexit relegated to the sidelines — but then he delivers his conclusions. They ostensibly concern minimising “nuclear/bio/AI risks and the potential for disastrous climate change”, but the implications for his Brexit strategy are irresistible.

Cummings feels we need:

1. Different ‘models for effective action’ among powerful people, which will only happen if either (A) some freak individual/group pops up, probably in a crisis environment or (B) somehow incentives are hacked. (A) can’t be relied on and (B) is very hard.

2. A new institution with global reach that can win global trust and support is needed. The UN is worse than useless for these purposes.

3. Public opinion will have to be mobilised to overcome the resistance of political Insiders, for example, regarding the potential for technology to bring very large gains ‘to me’ and simultaneously avert extreme dangers. This connects to the very widespread view that a) the existing economic model is extremely unfair and b) this model is sustained by a loose alliance of political elites and corporate looters who get richer by screwing the rest of us.

It’s reasonable to conclude this is as much about Brexit as about anything else, and that he believes workable solutions to the impasse cannot come about — nor can the establishment figures that he claims seek to block them be circumvented — unless we reach a crisis environment, which can only mean the precipice of a no-deal exit.

“In some possible branches of the future leaving will be an error.”

As Stephen Bush argues, it’s very unlikely that actually leaving without a deal is his preferred endgame. On Wednesday, Cummings implicitly seemed to back it, telling a Sky News reporter that “politicians don’t get to choose which votes they respect”. But even before the referendum, in a remarkably prescient 2015 blog, he acknowledged: “Creating an exit plan that makes sense and which all reasonable people could unite around seems an almost insuperable task.” Indeed, on his now-deleted Twitter account, he even announced: “In some possible branches of the future leaving will be an error”.

But how can there be a different outcome? The fact that Cummings has posted hundreds of thousands of words online makes his silence on some subjects all the more deafening. On the Irish border, for example, he simply has this to say:

The Government has also aided and abetted bullshit invented by Irish nationalists and Remain campaigners that the Belfast Agreement prevents reasonable customs checks on trade between Northern Ireland and the Republic. Read the agreement. It does no such thing. This has fatally undermined the UK’s negotiating position and has led to the false choice of not really leaving the EU (‘the Government’s backstop’) or undermining the UK’s constitutional integrity (‘the EU’s backstop’).

His reading is both correct and unhelpful. The agreement itself might not prevent checks — but that’s not the point. He doesn’t engage with the more important issue of whether customs checks would be damaging for the wider peace process and, if so, what solutions exist.

On trade he has even less to say. Others have noted that in 2017, he claimed he got involved in the referendum campaign precisely because he feared that free trade would end as a result of people growing disillusioned with the movement of low-skilled people within the European Union, but he has yet to express a vision for how he wants it to work in a post-EU world. In 2015, everything from a deal to remaining in the European Economic Area seemed to be on the table, as far as he was concerned.

It’s unclear whether he’s merely keeping his powder dry or whether he has no answer on such issues. Here he rages about the lack of Brexit planning before teasing how this blog explains “some of what needs to be done”. It offers some thoughts on America’s Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) in the '60s and '70s, in which he asks, “What does a process that produces ideas that change the world look like?” The answer: “We need a motivating vision aimed not at tomorrow but at changing the basic wiring of the whole system, a vision that can align ‘the little iron filings’, and then start building for the long-term.

“I will go into what I think this vision could be and how to do it another day,” he adds.

If that day did ever come, it was perhaps here, where he writes about a better system for government. It’s a long way from offering any practicalities.

Likely, he is wisely keeping certain views to himself. His greatest ire, of course, is reserved for the Brexiteer backbenchers who talked down the risks posed by no deal in the early days, and even celebrated the arrival of the backstop. But he never criticises the Brexit-backing ministers who did similarly. It’s almost as if he suspected he might end up working with these people.

Most likely, he doesn’t think it matters. In fact, a Twitter exchange all but confirms this to be the case. For Cummings, all that matters right now is getting the civil service in shape to deliver a no-deal Brexit. The rest of the plan will fall into place once that task is complete.

A Whitehall source says that, despite the fire and fury regarding the civil servants in his blogs, and the fear he has instilled in special advisers, the initial noises from Number 10 towards civil servants have been rather more conciliatory than imagined.

This might sound surprising but squares with the blogs. While the most senior “courtier-fixers”, such as Olly Robbins and Jeremy Heywood, are lambasted (unlike “people with models for truly effective action like General Groves”), Cummings’ anger is reserved for the system more than with the individuals who inhabit it. Nowhere is his capacity for brilliance demonstrated so closely alongside the sloppiness of his thought than on this subject.

Most of his writing is concerned with the need for better, data-informed policymaking, as well as more streamlined, high-functioning teams with lots of creative autonomy. Few could argue with this assessment:

Political ‘debate’ and the processes of government are largely what they have always been — largely conflict over stories and authorities where almost nobody even tries to keep track of the facts/arguments/models they’re supposedly arguing about, or tries to learn from evidence, or tries to infer useful principles from examples of extreme success/failure.

Some feel the worrying thing about Cummings is less how he wants to innovate and more how he approaches problems. The blogs show a magpie-like capacity for digging up obscure, interesting practices and individuals, but don’t offer nuanced or critical appraisal; they end up whisked into a narrative that casts various private-sector visionaries up against a monolithic civil service. His arguments on outsourcing, for example, which he keeps on returning to throughout the blogs as an example of something we can improve after Brexit, are semi-informed at best.

He is furious about Whitehall’s role in enabling gigantic “corporate looters” of industry, like Carillion, but shows little understanding of the exact nature of the problem: the way the broken nature of the market is satisfying neither government nor contractor, the way supply and demand has evolved over the last few decades, the way the government has tried to help small and medium-sized enterprises get involved, the lack of alternative options when it comes to running something like a prison, and so on.

The problem is more complex than his characterisation of incompetent civil servants being conned by unscrupulous businesses. He goes on to incorrectly state that “nothing” has changed with the relationship between the companies and government; in fact, plenty has. For all his fury, he offers nothing by way of practical solutions to the issues he identifies. It’s this lack of serious engagement ahead of working in Number 10, where he’s likely to face challenges that are a great deal more complex, which concerns insiders.

“The better educated think that psychological manipulation is something that happens to ‘the uneducated masses’ but they are extremely deluded.”

One Whitehall source, pointing out that there’s more to government than what Cummings saw at the Department for Education, acerbically noted that the bureaucracy he despises exists to stop poor performances such as departments producing error-strewn financial statements. This was something Cummings’ own department did. Another source familiar with his work offered a particularly withering assessment, describing him as “a man with a history degree — who has seen Terminator.”

Part of the issue is his apparent unwillingness to learn from examples that don’t fit with his preconceptions. In his blogs, he rails against poor performance and civil service inaction, but there’s no room for, say, the secret contingency planning that saved the 2012 Olympics from a potential disaster due to a private company’s failings, the work that has stopped countless terror attacks — or the fact that many of our worst modern disasters (Grenfell Tower and the 2008 financial crisis, to name two) occur precisely because there aren’t enough of the checks and balances he so frequently bemoans.

Cummings is intrigued with the concept of which stories our policymakers believe — at one point he claims, “The better educated think that psychological manipulation is something that happens to ‘the uneducated masses’ but they are extremely deluded,” and he may well be right.

A combination of bad journalism and televised fiction has left many people believing this story: A madcap genius who single-handedly delivered the 2016 referendum result (something he disputes himself) is set to upend the entirety of Whitehall and make us crash out of the EU with no deal. A close look at Cummings’ output suggests his role in whatever happens next may be rather less inspired, and rather less dramatic.